The Devil's Dinner: A Gastronomic and Cultural History of Chili Peppers

Stuart Walton

History, food

What irritated me most about The Devil's Dinner was the organization. The chapters are arranged without any real narrative flow, information is sometimes repeated, and the whole thing comes off as something of a muddle. Nor did I think that the research that went into the book was especially deep or complete; Walton seems to have relied heavily on a small number of interviews and a lot of second-hand reportage.

That said, there's some interesting stuff in here. The "burning" sensation of chili, for example, really does activate some of the same neural pathways as actual burning. Also, there's a real thing out there called Male Idiot Theory, which has been used to explain chili-eating contests. I'll buy it.

Rather surprisingly, there's no recipe section.

Overall verdict: mildly interesting. But with a title and topic like this, "mild" shouldn't be the descriptor! I'd pay good money to see John McPhee do for the chili pepper what he did for Oranges, for example.

Showing posts with label Sociology. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Sociology. Show all posts

Sunday, May 12, 2019

Wednesday, April 3, 2019

Book Review: The World of the Shining Prince

The World of the Shining Prince: Court Life in Ancient Japan

Ivan Morris

History, Sociology

An extraordinarily complete and encompassing view of something odd and beautiful. Heian-period Japan--c. AD 1000--developed a court society that was, in some ways, unique. For the tiny aristocratic elite, what counted was aesthetics (and lineage, but that's not the unique part). Not the warrior virtues, not competence, not money, not power, but beauty and culture were the currency. The nominal government didn't govern. The police and the army were largely ineffectual. Nobles spent their days in composing poems for one another, judging perfumes, conducting polygamous affairs (according to ritualized patterns), and honing their appreciation of the transitory nature of life. I find it hard to imagine that such a society could have survived long except on an island.

Ivan Morris's prose isn't brilliant, but it's serviceable. He does an amazing job bringing the Heian court to life in all of its details; you can open to any random page and find something worth knowing. Page 137: "One of the most important and active offices in the Ministry of Central Affairs was the Bureau of Divination". Page 80: "Emperor Ichijo's pet cat was awarded the theoretical privilege of wearing the head-dress (koburi) reserved for members of the Fifth Rank and above." Page 235: "The official concubine may be chosen in various ways." Morris is also pretty good at pointing out parallels from more familiar Western examples, as well as pointing out where the parallels are misleading or nonexistent.

I read The World of the Shining Prince because I was going to see an exhibition on The Tale of Genji (he's the Shining Prince, for those of you keeping score at home). It didn't make my must-recommend list, but for anyone trying to understand Heian Japan it's indispensable.

Ivan Morris

History, Sociology

An extraordinarily complete and encompassing view of something odd and beautiful. Heian-period Japan--c. AD 1000--developed a court society that was, in some ways, unique. For the tiny aristocratic elite, what counted was aesthetics (and lineage, but that's not the unique part). Not the warrior virtues, not competence, not money, not power, but beauty and culture were the currency. The nominal government didn't govern. The police and the army were largely ineffectual. Nobles spent their days in composing poems for one another, judging perfumes, conducting polygamous affairs (according to ritualized patterns), and honing their appreciation of the transitory nature of life. I find it hard to imagine that such a society could have survived long except on an island.

Ivan Morris's prose isn't brilliant, but it's serviceable. He does an amazing job bringing the Heian court to life in all of its details; you can open to any random page and find something worth knowing. Page 137: "One of the most important and active offices in the Ministry of Central Affairs was the Bureau of Divination". Page 80: "Emperor Ichijo's pet cat was awarded the theoretical privilege of wearing the head-dress (koburi) reserved for members of the Fifth Rank and above." Page 235: "The official concubine may be chosen in various ways." Morris is also pretty good at pointing out parallels from more familiar Western examples, as well as pointing out where the parallels are misleading or nonexistent.

I read The World of the Shining Prince because I was going to see an exhibition on The Tale of Genji (he's the Shining Prince, for those of you keeping score at home). It didn't make my must-recommend list, but for anyone trying to understand Heian Japan it's indispensable.

Sunday, January 13, 2019

Book Review: Capitalism in America

Capitalism in America: A History

Alan Greenspan, Adrian Wooldridge

Economics, history

Capitalism: Alan Greenspan is for it!

No, that's not the whole review. For the first half of Capitalism in America I thought that it might be, though. That's the half that's purely descriptive. It's stuffed full of statistics, sure enough, and not badly written, but it's a fairly standard economic history of the U.S. into the early 20th century. I already knew that railroads were important, that slavery was bad, that Standard Oil was big; Capitalism in America added only some numbers to my knowledge, which I have since largely forgotten.

The book gets more interesting when the authors finally start constructing an argument, instead of a play-by-play. Thank the reformers, such as Theodore Roosevelt, who put the brakes on the laissez-faire free-for-all. Greenspan and Wooldridge have to come to grips with what they did, which forces them to assess the system's successes and failures. The result is a pretty good argument for capitalism, broadly speaking, as an engine for innovation and as a proven way of lifting people out of poverty.

That's not to say that I think their analysis is a complete success. On the contrary, I think it's open to some fairly serious criticism. For example, Capitalism in America rightly contains some ringing denunciations of the slave economy. Good for you, gentlemen! But nowhere--literally nowhere--does it acknowledge that this country's 19th-century prosperity was based on spending down a metaphorical trust fund, consisting of land that had been looted from its native inhabitants. It's easy to make one group (white settlers) prosperous by making another group (Native Americans) poor. How much should we credit that to the success of capitalism vs. the profits of theft? Greenspan and Wooldridge are silent.

Similarly, G&W are decidedly . . . let's say "myopic" . . . when it comes to their critique of the New Deal. They make a fuss, several times over, about the fact that the New Deal recovery under FDR was interrupted by a second downturn in 1937. They do not see fit to mention that many other economists blame that downturn on FDR's premature decision to end a lot of New Deal spending in favor of balancing the budget. They also fall into the classic trap of saying that "It wasn't government spending that ended the Depression; it was World War II." Okay, and World War II did this how? Hint: who paid for all of those tanks, airplanes, salaries, jeeps, Liberty Ships, prophylactics, bullets, cans of Spam, uniforms, etc.? Could it have been the U.S. government? Why, I believe it could!

Perhaps the most telling small indicator of this myopia comes near the very end of Capitalism in America. "There were good reasons for complaining" about the effects of industrial capitalism, the authors concede. . "Deaths from industrial accidents in Pittsburgh per 100,000 residents almost doubled . . . between 1870 and 1900." Then, in the very next sentence, "Politicians such as Teddy Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson whipped up all this discontent into successful political movements" (emphasis added). Note that verb phrase. Now, "whipped up" is a dismissive phrase. The strong implication is that those people who were complaining about the doubling of the death rate were a bunch of slow-witted hoi polloi malcontents, who--instead of being property grateful for the beneficence of their betters--were so crass as to actually agitate for a larger share of the fruits of their labor. The nerve! What right did they have to interfere with the process of accumulating wealth, by questioning the purposes for which the wealth was accumulated?

What's particularly ironic is that it's a version of an argument that southern slaveholders used. Chattel slavery (they avowed) made the country richer as a whole. If some people were the losers in that process, well, too bad for them. Greenspan and Wooldridge would surely have no truck with that version of history; but when it comes to more recent developments they are blind to the parallel.

In the end, Capitalism in America is what I'd call tactically convincing. Its final argument--in favor of "creative destruction" (a cliche that the book rather overuses), and against the growth in entitlements and regulation--is well put, and well-supported by facts. I'm not unsympathetic. It's easy to close the book thinking, "well, that makes sense." But I've read other books that take the same facts, put a different slant on them, and evoke the same reaction towards a quite different set of policies. It's worth reading, but not worth accepting uncritically.

One of the best books on finance out there is Liaquat Ahamed's The Lords of Finance, focusing specifically on the role of central bankers and the gold standard in bringing on the Great Depression. Broader, and also excellent, is Nicholas Wapshott's Keynes/Hayek: The Clash That Defined Modern Economics.

Also, G&W refer several times to Richard White's The Republic for Which It Stands. I didn't like the latter book much, but I have to say that future historians could be pardoned for thinking that it was describing a completely different country than the one in Capitalism in America.

Alan Greenspan, Adrian Wooldridge

Economics, history

Capitalism: Alan Greenspan is for it!

No, that's not the whole review. For the first half of Capitalism in America I thought that it might be, though. That's the half that's purely descriptive. It's stuffed full of statistics, sure enough, and not badly written, but it's a fairly standard economic history of the U.S. into the early 20th century. I already knew that railroads were important, that slavery was bad, that Standard Oil was big; Capitalism in America added only some numbers to my knowledge, which I have since largely forgotten.

The book gets more interesting when the authors finally start constructing an argument, instead of a play-by-play. Thank the reformers, such as Theodore Roosevelt, who put the brakes on the laissez-faire free-for-all. Greenspan and Wooldridge have to come to grips with what they did, which forces them to assess the system's successes and failures. The result is a pretty good argument for capitalism, broadly speaking, as an engine for innovation and as a proven way of lifting people out of poverty.

That's not to say that I think their analysis is a complete success. On the contrary, I think it's open to some fairly serious criticism. For example, Capitalism in America rightly contains some ringing denunciations of the slave economy. Good for you, gentlemen! But nowhere--literally nowhere--does it acknowledge that this country's 19th-century prosperity was based on spending down a metaphorical trust fund, consisting of land that had been looted from its native inhabitants. It's easy to make one group (white settlers) prosperous by making another group (Native Americans) poor. How much should we credit that to the success of capitalism vs. the profits of theft? Greenspan and Wooldridge are silent.

Similarly, G&W are decidedly . . . let's say "myopic" . . . when it comes to their critique of the New Deal. They make a fuss, several times over, about the fact that the New Deal recovery under FDR was interrupted by a second downturn in 1937. They do not see fit to mention that many other economists blame that downturn on FDR's premature decision to end a lot of New Deal spending in favor of balancing the budget. They also fall into the classic trap of saying that "It wasn't government spending that ended the Depression; it was World War II." Okay, and World War II did this how? Hint: who paid for all of those tanks, airplanes, salaries, jeeps, Liberty Ships, prophylactics, bullets, cans of Spam, uniforms, etc.? Could it have been the U.S. government? Why, I believe it could!

Perhaps the most telling small indicator of this myopia comes near the very end of Capitalism in America. "There were good reasons for complaining" about the effects of industrial capitalism, the authors concede. . "Deaths from industrial accidents in Pittsburgh per 100,000 residents almost doubled . . . between 1870 and 1900." Then, in the very next sentence, "Politicians such as Teddy Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson whipped up all this discontent into successful political movements" (emphasis added). Note that verb phrase. Now, "whipped up" is a dismissive phrase. The strong implication is that those people who were complaining about the doubling of the death rate were a bunch of slow-witted hoi polloi malcontents, who--instead of being property grateful for the beneficence of their betters--were so crass as to actually agitate for a larger share of the fruits of their labor. The nerve! What right did they have to interfere with the process of accumulating wealth, by questioning the purposes for which the wealth was accumulated?

What's particularly ironic is that it's a version of an argument that southern slaveholders used. Chattel slavery (they avowed) made the country richer as a whole. If some people were the losers in that process, well, too bad for them. Greenspan and Wooldridge would surely have no truck with that version of history; but when it comes to more recent developments they are blind to the parallel.

In the end, Capitalism in America is what I'd call tactically convincing. Its final argument--in favor of "creative destruction" (a cliche that the book rather overuses), and against the growth in entitlements and regulation--is well put, and well-supported by facts. I'm not unsympathetic. It's easy to close the book thinking, "well, that makes sense." But I've read other books that take the same facts, put a different slant on them, and evoke the same reaction towards a quite different set of policies. It's worth reading, but not worth accepting uncritically.

One of the best books on finance out there is Liaquat Ahamed's The Lords of Finance, focusing specifically on the role of central bankers and the gold standard in bringing on the Great Depression. Broader, and also excellent, is Nicholas Wapshott's Keynes/Hayek: The Clash That Defined Modern Economics.

Also, G&W refer several times to Richard White's The Republic for Which It Stands. I didn't like the latter book much, but I have to say that future historians could be pardoned for thinking that it was describing a completely different country than the one in Capitalism in America.

Friday, September 14, 2018

Book Review: Germany

Germany: Memories of a Nation

Neil MacGregor

History, sociology

This book works better than it has any right to. MacGregor's thesis is that it's impossible to write the history of Germany, because for most of history there hasn't been a single "Germany". The Holy Roman Empire overlapped with "Germany", but it wasn't the same, and the empire itself was a jigsaw puzzle of little Mini-Germanies. (As late as the 18th century, most of them had their own currencies.) Various historically-German-speaking regions and cities are now parts of other countries. The German Empire only lasted from 1871 to 1918, and the middle of its three emperors only reigned for 90 days. There were two actual Germanies from 1945 to 1990. And these are just the political fragmentations!

So MacGregor wrote a book about how various things, places, people, and ideas have been used to construct an idea--the titular "memories"--of Germany. Often the same subjects are used in multiple ways: the sculptor Tilman Riemenschneider got stamps from both East and West Germany, for example, with quite different messaging. It would be frightfully easy to turn this material into a mess. How can you write one book that encompasses the Iron Cross, the VW Beetle, Charlemagne's crown, the gates at Buchenwald, porcelain, the psychology of the forest, and the defeat of the Roman Legions in AD 9?

Somehow it all works. It doesn't hurt that the individual chapters are excellent little mini-essays in the mold of James Burke's Connections, or that the theme--the manufacture and use of "memories"--is consistently sustained. It's a remarkable stained-glass-window, adding up to more than the sum of its excellent parts. If it never does resolve the twists and contradictions of this thing called "Germany" . . . .well, that's sort of the point.

Neil MacGregor

History, sociology

This book works better than it has any right to. MacGregor's thesis is that it's impossible to write the history of Germany, because for most of history there hasn't been a single "Germany". The Holy Roman Empire overlapped with "Germany", but it wasn't the same, and the empire itself was a jigsaw puzzle of little Mini-Germanies. (As late as the 18th century, most of them had their own currencies.) Various historically-German-speaking regions and cities are now parts of other countries. The German Empire only lasted from 1871 to 1918, and the middle of its three emperors only reigned for 90 days. There were two actual Germanies from 1945 to 1990. And these are just the political fragmentations!

So MacGregor wrote a book about how various things, places, people, and ideas have been used to construct an idea--the titular "memories"--of Germany. Often the same subjects are used in multiple ways: the sculptor Tilman Riemenschneider got stamps from both East and West Germany, for example, with quite different messaging. It would be frightfully easy to turn this material into a mess. How can you write one book that encompasses the Iron Cross, the VW Beetle, Charlemagne's crown, the gates at Buchenwald, porcelain, the psychology of the forest, and the defeat of the Roman Legions in AD 9?

Somehow it all works. It doesn't hurt that the individual chapters are excellent little mini-essays in the mold of James Burke's Connections, or that the theme--the manufacture and use of "memories"--is consistently sustained. It's a remarkable stained-glass-window, adding up to more than the sum of its excellent parts. If it never does resolve the twists and contradictions of this thing called "Germany" . . . .well, that's sort of the point.

Wednesday, July 25, 2018

Book Review: The Amorous Heart

The Amorous Heart: An Unconventional History of Love

Marilyn Yalom

History, sociology

No, I haven't taken to reading Harlequin Romances. The Amorous Heart is an odd little book about . . . um . . . the way the idea and image of "the heart" have been used to symbolize romance through the ages. Sort of.

I liked The Amorous Heart. I'm not quite sure who else would like it. It's not sufficiently scholarly for an academic readership. It's not zippy enough for a popularization (though it's quite readable). It doesn't go deep on a single, identifiable subject, the way the biography-of-a-substance subgenre does. It's chronological in organization, but its material wanders around from the history of the 💗symbol to the Roman de la Rose to the Valentine's Day industry. I guess I'd recommend it to anyone who's got a certain amount of free-floating curiosity and is willing to attach it to more or less any subject.

Marilyn Yalom

History, sociology

No, I haven't taken to reading Harlequin Romances. The Amorous Heart is an odd little book about . . . um . . . the way the idea and image of "the heart" have been used to symbolize romance through the ages. Sort of.

I liked The Amorous Heart. I'm not quite sure who else would like it. It's not sufficiently scholarly for an academic readership. It's not zippy enough for a popularization (though it's quite readable). It doesn't go deep on a single, identifiable subject, the way the biography-of-a-substance subgenre does. It's chronological in organization, but its material wanders around from the history of the 💗symbol to the Roman de la Rose to the Valentine's Day industry. I guess I'd recommend it to anyone who's got a certain amount of free-floating curiosity and is willing to attach it to more or less any subject.

Saturday, March 3, 2018

Book Review: The Wizard and the Prophet

The Wizard and the Prophet: Two Remarkable Scientists and Their Dueling Visions to Shape Tomorrow's World

Charles C. Mann

Science, biography, ecology, philosophy, politics

[DISCLAIMER: Charles C. Mann graduated from my alma mater and lives in my home town. I don't think we've ever met, but it would be surprising if we didn't have connections in common.]

It's quite likely that The Wizard and the Prophet will be my favorite book of 2018.

Here's the core of the matter: in thirty years, the world will have ten billion people. Should we:

Most importantly, Mann is scrupulously fair towards both Wizards and Prophets. He presents each sides's arguments fairly and in their best lights, and then presents the other side's critique with equal insight. That lifts the book up from "enjoyable" to "important". These are big ideas, and they are consequential. How we think about them will have a profound effect on life on earth--within our lifetimes.

It subtracts nothing from Mann's wonderful book to point out that the dichotomy he points out is an artificial one. "The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing": Prophets and Wizards are hedgehogs, but the answer probably lies with the foxes. It's true that we should waste less, decentralize our electrical grid, be skeptical of claims that innovation will inevitably save us. It's also true that innovation has produced miracles, that more people are living better now than ever before, that the doomsayers have hitherto been wrong. We should recognize both truths.

Related books worth reading are Gretchen Bakke's The Grid, Rose George's The Big Necessity, and Edward Glaeser's The Triumph of the City. Mann's own 1491 and 1493, though unrelated, are also good.

Charles C. Mann

Science, biography, ecology, philosophy, politics

[DISCLAIMER: Charles C. Mann graduated from my alma mater and lives in my home town. I don't think we've ever met, but it would be surprising if we didn't have connections in common.]

It's quite likely that The Wizard and the Prophet will be my favorite book of 2018.

Here's the core of the matter: in thirty years, the world will have ten billion people. Should we:

- Make wise use of our existing resources, conserving and cutting back as necessary, in order to minimize the damage we cause to ourselves and our planet? That's the "Prophet" response, exemplified in Mann's book by the early ecologist William Vogt.

- Innovate, adapt, embracing creativity and dynamic capitalism, in order to expand the carrying capacity of the world and lift more people out of poverty? That's the "Wizard" response, as espoused by Norman Borlaug--a man who won a Nobel Peace Prize as the father of the so-called "Green Revolution".

Most importantly, Mann is scrupulously fair towards both Wizards and Prophets. He presents each sides's arguments fairly and in their best lights, and then presents the other side's critique with equal insight. That lifts the book up from "enjoyable" to "important". These are big ideas, and they are consequential. How we think about them will have a profound effect on life on earth--within our lifetimes.

It subtracts nothing from Mann's wonderful book to point out that the dichotomy he points out is an artificial one. "The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing": Prophets and Wizards are hedgehogs, but the answer probably lies with the foxes. It's true that we should waste less, decentralize our electrical grid, be skeptical of claims that innovation will inevitably save us. It's also true that innovation has produced miracles, that more people are living better now than ever before, that the doomsayers have hitherto been wrong. We should recognize both truths.

Related books worth reading are Gretchen Bakke's The Grid, Rose George's The Big Necessity, and Edward Glaeser's The Triumph of the City. Mann's own 1491 and 1493, though unrelated, are also good.

Sunday, October 8, 2017

Book Review: Grocery

Grocery: The Buying and Selling of Food in America

Michael Ruhlman

Sociology, Food

The blurb describes Grocery as a "mix of personal history, social commentary, food rant, and immersive journalism." That's a pretty good capsule description. It leaves out the fact that some of those components are better than others.

The food rant is the worst. It's nothing but a combination of conventional foodie wisdom and personal prejudices. It talks a lot about trends in food, in a way that's very convincing if you ignore that fraction of the American public that doesn't happen to live in Brooklyn. You will not find, for example, any acknowledgment that organic accounts for all of 4% of U.S. food sales. What you will find is Mr. Crankypants-style assertions like "Canola stands for Canadian oil association--that's not food," which blithely disregards the fact that "canola" is in fact nothing more than a conventionally-bred form of the ancient crop traditionally known as rapeseed.

By contrast, the glimpse inside the day-to-day working of a modest-sized regional grocery chain (Heinen's, in the Cleveland area) is fascinating. Ruhlman got a tremendous level of access and cooperation from the Heinen family, and he does a great job of walking us through the things that they deal with. How do you set up the store? How do you compete with bigger chains when everyone has the same corn flakes? How is food buying and food selling changing? To give you an idea of how enticing this is, I now kind of want to go to Cleveland in order to go to a grocery store--specifically, this grocery store.

Finally, Ruhlman also does a wonderful job mixing in his own personal narrative. Chapter 1, entitled "My Father's Grocery-Store Jones," opens like this:

Michael Ruhlman

Sociology, Food

The blurb describes Grocery as a "mix of personal history, social commentary, food rant, and immersive journalism." That's a pretty good capsule description. It leaves out the fact that some of those components are better than others.

The food rant is the worst. It's nothing but a combination of conventional foodie wisdom and personal prejudices. It talks a lot about trends in food, in a way that's very convincing if you ignore that fraction of the American public that doesn't happen to live in Brooklyn. You will not find, for example, any acknowledgment that organic accounts for all of 4% of U.S. food sales. What you will find is Mr. Crankypants-style assertions like "Canola stands for Canadian oil association--that's not food," which blithely disregards the fact that "canola" is in fact nothing more than a conventionally-bred form of the ancient crop traditionally known as rapeseed.

By contrast, the glimpse inside the day-to-day working of a modest-sized regional grocery chain (Heinen's, in the Cleveland area) is fascinating. Ruhlman got a tremendous level of access and cooperation from the Heinen family, and he does a great job of walking us through the things that they deal with. How do you set up the store? How do you compete with bigger chains when everyone has the same corn flakes? How is food buying and food selling changing? To give you an idea of how enticing this is, I now kind of want to go to Cleveland in order to go to a grocery store--specifically, this grocery store.

Finally, Ruhlman also does a wonderful job mixing in his own personal narrative. Chapter 1, entitled "My Father's Grocery-Store Jones," opens like this:

Rip Ruhlman loved to eat, almost more than anything else. We'd be tucking in to the evening's meal when he'd ask, with excitement in his eyes, "What should we have for dinner tomorrow?" Used to drive Mom crazy. And because he loved to eat, my father loved grocery stores.This touching family story is threaded neatly through the book. It makes up for the boring food rant segments. It makes Grocery more than the sum of its parts. It's about the grocery business, yes, but it's also about what food means to us.

Thursday, September 7, 2017

Book Review: Empire of Things

Empire of Things: How We Became a World of Consumers, from the Fifteenth Century to the Twenty-First

Frank Trentmann

Sociology, economics

At the end of Empire of Things you'll find 107 pages of densely-packed, small-print end notes. You'll also find an apologetic note from the author:

Page 326-327:

Frank Trentmann

Sociology, economics

At the end of Empire of Things you'll find 107 pages of densely-packed, small-print end notes. You'll also find an apologetic note from the author:

. . . these are only the tip of the research iceberg on which this book rests. Readers who wish to delve deeper . . .can browse my 260-page working bibliography at: http://www.bbk.ac.uk/frank-trentmann/empire-of-things/.This, mind you, after 692 pages of text. These aren't light, fluffy pages, either. It's like you're walking into Dr. Trentmann's Famous Museum of Consumer Facts. Imagine a long room, lined with glass cases, each of which is crammed with exhibits, and where each exhibit has an explanatory plaque which you're expected to read. A semi-random trawl through the book's first half furnishes some examples. Page 175:

In 1800, Paris and London made do with a few thousand oil lamps . . . By 1867 . . . Paris was lit by around 20,0000 gas lamps. By 1907, it had 54,000; London had as many as 77,000 lights . . . each burnt 140 litres of gas a night. When the First World War broke out in 1914, Paris was seventy times brighter than during the 1848 revolution.Page 212:

A typical local Varieté cinema in 1904 showed moving pictures to around 70,000 viewers a week . . . Lexington, Kentucky had two cinemas for its 25,000 inhabitants . . . By 1914, Britain had 3,800 cinemas. London alone had almost five hundred, with seating for 400,000, more than five times that in music halls . . . 250,000 Londoners went to the cinema, every day. In New York City, the weekly attendance was closer to a million . . .Page 239:

. . . a factory worker typically earned $590 in 1890 . . . almost a million new homes were constructed in 1925 alone . . . In New York and Philadelphia, 87 per cent and 61 per cent were renting in 1920. In 1930, this was down to 80 per cent and 42 per cent.

Page 326-327:

. . . in the early 1960s, public expenditure was 36 per cent of GDP in France (33 per cent in the UK; 35 per cent in West Germany); by the late 1970s it had reached 46 per cent in all three . . . In the USSR, consumer durables grew at a rate of 8 per cent a year . . . the Hungarian government promised its people 610,000 TVs, 600,000 washing machines and 128,000 fridges within the next three years . . .It's not that the facts aren't interesting; they are. It's not that Empire of Things is badly written, either, although someone should let Frank Trentmann know that it's no longer a flogging offense to use a contraction now and then. It's just that there's so . . . damn . . . much of it. Even the most dedicated reader isn't going to retain more than a tiny fraction of this information. Empire of Things would have been so much more memorable if it had only concentrated on telling a story. (The second half, which is organized by concept rather than chronologically, is a bit better than the first.) But if there's a theme running through the book, it's one that only really becomes clear in the final 20 pages or so. The book is intriguing in spots, and enlightening in spots, but as a whole it's something of a blur.

Friday, July 7, 2017

Book Review: The Ground Beneath Us

The Ground Beneath Us: From the Oldest Cities to the Last Wilderness, What Dirt Tells Us About Who We Are

Paul Bogard

Nature, philosophy

Back in December, as mymany regular readers may recall, I read a book called Of Beards and Men. I disagreed with most of the author's conclusions, but I liked the book anyway. With The Ground Beneath Us I had the opposite reaction. There's scarcely a sentiment--scarcely a sentence--I disagreed with. But I didn't like the book.

The basic problem is that The Ground Beneath Us is a purely Romantic exercise in prose styling. It's long on lyricism, it's long on passion, but it's quite devoid of intellect. Bogard is the kind of author who thinks that name-checking famous writers (Thoreau! Muir!) is enough to qualify him as profound. He likes scare quotes. He cites big frightening-looking numbers without giving any context. He believes unquestioningly that "indigenous" is an exact and infallible synonym for "noble". He uncritically parrots false equivalencies.

And he abuses statistics. In my book, this is an unforgivable sin. For example, there's this:

Finally, even granting the righteousness of Bogard's propaganda, he's absolutely lacking in any concrete intellectual proposals. Agreed: global warming bad, urban sprawl bad, resource depletion bad, habitat loss bad. So what? What should we do about it? Bogard's answer to this appears to be some kind of mystical transcendence involving "knowing the connections that keep us alive". The word "sacred" gets thrown around a lot. (It's probably indigenous.) What this amounts to is a refusal to face up to the plain facts:

Failing that, Bogard's only logically consistent position would be to hope for a plague that kills off a good fraction of the human race. I bet he won't own up to that one, though.

Paul Bogard

Nature, philosophy

Back in December, as my

The basic problem is that The Ground Beneath Us is a purely Romantic exercise in prose styling. It's long on lyricism, it's long on passion, but it's quite devoid of intellect. Bogard is the kind of author who thinks that name-checking famous writers (Thoreau! Muir!) is enough to qualify him as profound. He likes scare quotes. He cites big frightening-looking numbers without giving any context. He believes unquestioningly that "indigenous" is an exact and infallible synonym for "noble". He uncritically parrots false equivalencies.

And he abuses statistics. In my book, this is an unforgivable sin. For example, there's this:

While the percentage of population density increase in the United States since 1940 has been 113 percent, around national parks it has been nearly double that, at 224 percent . . . 210 percent around Glacier and 246 percent around Yellowstone . . . 3,000 percent around Mojave National Preserve . . .Here's the thing. National Parks, for some strange reason, tend to be located in sparsely populated areas. So a small increase in the absolute number of houses will seem like a large percentage. To take an extreme case, imagine that where there was one house in 1940, there are now six. That's a 500 percent increase! OMG! To the barricades! Or, to use Bogard's own example: one of the towns adjoining Mojave National Preserve is Baker, CA, population 735. For Baker to have grown by 3,000% since 1940, it would have had to have added about 700 houses. If you had added those same 700 houses to, say, Chicago, what percentage growth would that represent?

Finally, even granting the righteousness of Bogard's propaganda, he's absolutely lacking in any concrete intellectual proposals. Agreed: global warming bad, urban sprawl bad, resource depletion bad, habitat loss bad. So what? What should we do about it? Bogard's answer to this appears to be some kind of mystical transcendence involving "knowing the connections that keep us alive". The word "sacred" gets thrown around a lot. (It's probably indigenous.) What this amounts to is a refusal to face up to the plain facts:

- People in the developed world are not going to voluntarily go out and move en masse into organic free-range low-impact yurts.

- People in the developing world are not going to nobly and indigenously turn their backs on the kind of high-energy, high-impact Westernized lifestyle that they see people like me leading.

Failing that, Bogard's only logically consistent position would be to hope for a plague that kills off a good fraction of the human race. I bet he won't own up to that one, though.

Sunday, June 4, 2017

Book Review: Egyptomania

Egyptomania: A History of Fascination, Obsession and Fantasy

Ronald H. Fritze

History, sociology, archaeology

The very last sentence of Egyptomania is this:

As a compendium, Egyptomania is not without its charms. Fritze, although an academic, writes in good clear English rather than in High Academicese, and he displays an excellent sense of humor:

Finally, there's a lot of repetition. Also, things get repeated a lot. Not only that, the same basic facts are reiterated over and over. Halfway down page 134 we learn that "Renaissance Rome was the one place in the Europe of that era where a visitor could see and study a large number of Egyptian monuments and artefacts." At the bottom of the same page, we find out that "Rome was the one place in Europe where people could see a large amount of Egyptian artefacts without having to travel to Egypt." It's not just individual factoids; whole paragraphs are rehashed--if not quite so blatantly--two or three times over. This was vexing in Istanbul; in Egyptomania it's completely out of control.

As a resource for scholars, Egyptomania is admirably thorough. As a book for general readers, it's in need of some serious editorial TLC. It's not an unenjoyable read on the tactical level; as a whole, though, it will appeal mainly to the sort of reader who likes reading catalogs.

Ronald H. Fritze

History, sociology, archaeology

The very last sentence of Egyptomania is this:

Why Egypt is so attractive in popular culture remains something of a mystery, but its existence is undeniable.That's on page 377. Three hundred seventy seven pages is an awful lot of book to write (or read) without reaching a conclusion. Egyptomania is, basically, a 1.5-inch-thick Wikipedia "In Popular Culture" section. There are paragraphs, sections, and one entire chapter that could have been deleted without much loss. If the book isn't quite a list of everything everyone ever said or wrote or filmed about Egypt, it's not for want of trying.

As a compendium, Egyptomania is not without its charms. Fritze, although an academic, writes in good clear English rather than in High Academicese, and he displays an excellent sense of humor:

In the case of Isis Unveiled, the Masters provided precipitated pages of text The problem was that many of the precipitated pages had been copied from works by other writers without attribution. Someone had plagiarized and that person was either Blavatsky or one of those Masters. Since an ascended Master would never stoop to plagiarism, that leaves Madame Blavatsky.But I have to wonder what its editor was doing. For one thing, Egyptomania has a raft of basic copy-editing errors, including serial abuse and neglect of the common North American semicolon. For another, some of the book's assertions should have been gently fact-checked out of existence, such as the frankly bizarre statement that The Hound of the Baskervilles "drew its inspiration from the curse of the 'Unlucky Mummy.'" For a third, there are some exceedingly abrupt logical breaks and grammatical solecisms. Look again, for example, at that closing sentence quoted above. Grammatically, the "it" in "its existence is undeniable" can only refer to Egypt itself. While Egypt's existence is indeed undeniable, I don't think that's what Fritze meant to say.

Finally, there's a lot of repetition. Also, things get repeated a lot. Not only that, the same basic facts are reiterated over and over. Halfway down page 134 we learn that "Renaissance Rome was the one place in the Europe of that era where a visitor could see and study a large number of Egyptian monuments and artefacts." At the bottom of the same page, we find out that "Rome was the one place in Europe where people could see a large amount of Egyptian artefacts without having to travel to Egypt." It's not just individual factoids; whole paragraphs are rehashed--if not quite so blatantly--two or three times over. This was vexing in Istanbul; in Egyptomania it's completely out of control.

As a resource for scholars, Egyptomania is admirably thorough. As a book for general readers, it's in need of some serious editorial TLC. It's not an unenjoyable read on the tactical level; as a whole, though, it will appeal mainly to the sort of reader who likes reading catalogs.

Thursday, June 1, 2017

Book Review: Making It

[WARNING: long and slightly polemical.]

Making It: Why Manufacturing Still Matters

Louis Uchitelle

Politics, sociology

At the center of Making It there is an extremely acute observation: there is no such thing as laissez-faire manufacturing. There's always some kind of governmental support. This was true two centuries ago, when Samuel Slater avoided a British ban on exporting the designs of spinning machinery by memorizing how it worked. It was true in the 19th century, when tariffs protected U.S. industry and land grants supported the railroads. It's true now, when cities offer massive tax incentives to lure corporations.

To have no policy is itself a policy. That's what the federal government does now. As a result, the existing subsidy system is an incoherent mess of states and localities, all competing against one another. When companies build plants by looking for the biggest windfall, the result is not to create new jobs; it's just to move jobs from one place to another. This being the case, why not try to have a rational policy that promotes the common good?

Making It documents this observation with a wealth of statistics and facts. It documents, as well, the damage that the decline in manufacturing employment has wreaked. Unfortunately, it doesn't do nearly as good a job in analyzing what it's documented. The book's logic is a semi-random stew of non-sequiturs, circular arguments, and absurd prescriptions--and prescriptions is the word: Louis Uchitelle seems to be enamored of the top-down, there-oughta-be-a-law, Five Year Plan approach. He ought to be thinking in terms of incentives, not mandates. Mandates don't work. Incentives do. (Not, admittedly, always as designed.)

For instance, consider this excerpt (emphasis added):

Here's another one:

Those flaws are specific. Others are endemic. Making It repeatedly faults manufacturers for moving out of central cities, for instance, but its only proposed cure is this: ". . . government money . . . could have been used to keep manufacturers and distributors rooted in the cities by helping them pay for their operations." Except that, just a few pages earlier, a factory owner says flatly that even with these subsidies, "No, I would not move back. The biggest cost is attracting and training a workforce, and then once I've got three hundred people in place in St. Louis, someone's going to say, 'Let's organize a union'." In other words, the book is promoting a plan that by its own testimony wouldn't work.

Let's face reality: we're in a competitive, profit-driven economy, with every company in the world in the same race. The companies that don't make money go under. If Apple can't make a profit manufacturing cell phones, Apple will stop manufacturing cell phones. If Apple starts charging an extra $50 per phone to support a stateside factory, it will lose market share to their competitors that don't. If we could somehow mandate that every cell phone sold in the U.S. be made entirely in the U.S., then the U.S. will end up with overpriced, crappy cell phones, because every company on the planet will have a positive incentive to not sell their wares here.

(Aside: Louis Uchitelle depends a lot on argument by anecdote. Well, here's a counter-anecdote for him. My very own wife is a mechanical engineer who works in a factory. Her group is currently competing with a state-supported company in Italy, one with very much the kinds of policy supports that Uchitelle seems to prefer. Her outfit can't compete on price, because of the subsidies. Nonetheless, they're winning business from those competitors, because those competitors make lousy products.)

If Louis Uchitelle had gotten a tough-minded and thoughtful critique of his manuscript, Making It could have been a book with a lot of impact. Instead, it's a book that will appeal entirely who readers who already agree with its conclusions. Uchitelle is a reporter, and the reportage is excellent. The thinking is not.

Making It: Why Manufacturing Still Matters

Louis Uchitelle

Politics, sociology

At the center of Making It there is an extremely acute observation: there is no such thing as laissez-faire manufacturing. There's always some kind of governmental support. This was true two centuries ago, when Samuel Slater avoided a British ban on exporting the designs of spinning machinery by memorizing how it worked. It was true in the 19th century, when tariffs protected U.S. industry and land grants supported the railroads. It's true now, when cities offer massive tax incentives to lure corporations.

To have no policy is itself a policy. That's what the federal government does now. As a result, the existing subsidy system is an incoherent mess of states and localities, all competing against one another. When companies build plants by looking for the biggest windfall, the result is not to create new jobs; it's just to move jobs from one place to another. This being the case, why not try to have a rational policy that promotes the common good?

Making It documents this observation with a wealth of statistics and facts. It documents, as well, the damage that the decline in manufacturing employment has wreaked. Unfortunately, it doesn't do nearly as good a job in analyzing what it's documented. The book's logic is a semi-random stew of non-sequiturs, circular arguments, and absurd prescriptions--and prescriptions is the word: Louis Uchitelle seems to be enamored of the top-down, there-oughta-be-a-law, Five Year Plan approach. He ought to be thinking in terms of incentives, not mandates. Mandates don't work. Incentives do. (Not, admittedly, always as designed.)

For instance, consider this excerpt (emphasis added):

. . . in accepting the move to ATS [an outsourcing company], the mechanics lowered the odds that the two hundred or so assembly line workers they had left behind would have the leverage to organize a union and then bargain for higher wages and job security. While still on staff, the mechanics were in a position to support the assembly line workers by striking if the latter did, or by not striking but engaging in a work slowdown--dragging out repairs--if the company brought in outsiders to replace the assembly line workers. Without willing mechanics, a machinery breakdown can halt an assembly line in any factory and even shut it down. The Oplers [the company owners] understood this. "In our negotiations with ATS we specified that having skilled mechanics on all shifts and at all times was the reason for going with that company . . . We found that we could hold ATS to a higher standard than we were able to attain on our own."Do you see the trick here? The bolded sentences are being deployed to imply that the company moved its mechanics to ATS specifically in order to weaken employees' ability to strike. But the speaker doesn't say that. He just says that outsourcing gave them better availability. This is an artfully arranged synthesis, meant to support Making It's propaganda goals. It's not logic.

Here's another one:

Harley-Davidson . . . publicly declared in 201 that it would move some factory operations from Milwaukee, where it is headquartered, to a lower-wage city such as Stillwater, Oklahoma, or Kansas City, Missouri, if its hourly workers in Milwaukee failed to accept certain concessions . . . In the end, the regulars . . . gave in and ratified the contract, fearful they might lose their jobs altogether if Harley-Davidson carried out its threat to relocate. The city's taxpayers, however, were given no say in the matter--no opportunity to bat down Harley's threat--although their taxes helped to subsidize the company's operation in Milwaukee . . . [their] taxes should have given them a right to amend Harley's plan, and even to veto it by withholding subsidies from the company.Seriously? What does Louis Uchitelle imagine that the taxpayers could do? Pass a city ordinance forbidding Harley-Davidson from moving any jobs? Threaten to soak them with extra taxes on their Milwaukee operations? (That would go well, I'm sure.) Confiscate their HQ?

Those flaws are specific. Others are endemic. Making It repeatedly faults manufacturers for moving out of central cities, for instance, but its only proposed cure is this: ". . . government money . . . could have been used to keep manufacturers and distributors rooted in the cities by helping them pay for their operations." Except that, just a few pages earlier, a factory owner says flatly that even with these subsidies, "No, I would not move back. The biggest cost is attracting and training a workforce, and then once I've got three hundred people in place in St. Louis, someone's going to say, 'Let's organize a union'." In other words, the book is promoting a plan that by its own testimony wouldn't work.

Let's face reality: we're in a competitive, profit-driven economy, with every company in the world in the same race. The companies that don't make money go under. If Apple can't make a profit manufacturing cell phones, Apple will stop manufacturing cell phones. If Apple starts charging an extra $50 per phone to support a stateside factory, it will lose market share to their competitors that don't. If we could somehow mandate that every cell phone sold in the U.S. be made entirely in the U.S., then the U.S. will end up with overpriced, crappy cell phones, because every company on the planet will have a positive incentive to not sell their wares here.

(Aside: Louis Uchitelle depends a lot on argument by anecdote. Well, here's a counter-anecdote for him. My very own wife is a mechanical engineer who works in a factory. Her group is currently competing with a state-supported company in Italy, one with very much the kinds of policy supports that Uchitelle seems to prefer. Her outfit can't compete on price, because of the subsidies. Nonetheless, they're winning business from those competitors, because those competitors make lousy products.)

If Louis Uchitelle had gotten a tough-minded and thoughtful critique of his manuscript, Making It could have been a book with a lot of impact. Instead, it's a book that will appeal entirely who readers who already agree with its conclusions. Uchitelle is a reporter, and the reportage is excellent. The thinking is not.

Monday, January 9, 2017

Book Review: The Book

The Book: A Cover-to-Cover Exploration of the Most Powerful Object of Our Time

Keith Houston

History, books

The Book is a very good paean to, naturally, the book as physical object. Keith Houston chooses a clever and sensible arrangement. Rather than simply starting with cuneiform and moving forward, he traces the story of each of the book's components: the page (papyrus, parchment, paper), the text (writing and type), illustrations, and form. That turns out to be a dandy way of bringing together several separate but interrelated information streams.

Houston occasionally lapses into witticism of an notably English vintage. If you like this sort of thing, it's amusing; if you don't, it's merely arch. Other than that, his writing is good, his descriptions are clear, and his subject matter is first-rate.

Mark Kurlansky's Paper, for all of its lapses into highfalutin' nonsense, covers related topics. Also of interest: Henry Petroski's The Book on the Bookshelf (about how books have been stored) and Simon Garfield's Just My Type (fonts).

Keith Houston

History, books

The Book is a very good paean to, naturally, the book as physical object. Keith Houston chooses a clever and sensible arrangement. Rather than simply starting with cuneiform and moving forward, he traces the story of each of the book's components: the page (papyrus, parchment, paper), the text (writing and type), illustrations, and form. That turns out to be a dandy way of bringing together several separate but interrelated information streams.

Houston occasionally lapses into witticism of an notably English vintage. If you like this sort of thing, it's amusing; if you don't, it's merely arch. Other than that, his writing is good, his descriptions are clear, and his subject matter is first-rate.

Mark Kurlansky's Paper, for all of its lapses into highfalutin' nonsense, covers related topics. Also of interest: Henry Petroski's The Book on the Bookshelf (about how books have been stored) and Simon Garfield's Just My Type (fonts).

Tuesday, December 6, 2016

Book Review: Of Beards and Men

Christopher Oldstone-Moore

Sociology, history

[Warning: long and long-winded.]

Of Beards and Men is a humanist book in empiricist clothing. While it is indeed a "history of facial hair," it's also an academic's thesis about the meaning of facial hair. Oldstone-Moore says as much explicitly: "The most significant myth to be set aside is the notion that changes in facial hair are the meaningless product of fashion cycles."

When I call Of Beards and Men an academic's thesis, you might infer a certain . . . turgidity . . . of writing. Happily, that's not true in this case. The book doesn't have the level of levity and wit that one might expect from the title, but it's written in clear plain prose that's no trouble to read. The scholarship and research are excellent, and the illustrations are particularly apt. On the empiricist side, I have no quibbles.

Nor do I quarrel with the general thesis. Beards and shaving represent two different kinds of masculinity: "The clean-shaven face . . . has come to signify a virtuous and sociable man, whereas the beard marks someone as self-reliant and unconventional." That's a plausible high-level assessment, although it would be a stretch to apply it to every individual case.

Oldstone-Moore gets himself into a hairier (hah!) problem when he gets down to brass tacks, though. For one thing, this is a tremendously skewed volume. It could have been subtitled "The Revealing History of Facial Hair Among Western Cultural Elites." There's no mention of Africa, no mention of India, no mention of the Far East.

The class bias is forgivable when talking about ancient Sumeria. It's less forgivable by the time we reach the European Middle Ages. There are a good many period images of people who were not churchmen. For example:

Look! Some bearded peasants, some non-bearded peasants! Almost as if beardedness is an individual choice, or even the meaningless product of fashion cycles. For that matter, even kings get short shrift; Oldstone-Moore barely touches on the nobility, whom you'd think would be significant in any discussion of beard-as-masculine-signifier, even though their shaving habits changed markedly over the period.

It's not that Oldstone-Moore doesn't have written evidence. He does, and it clearly shows that some people started thinking differently about beards at some points. His error is to assume that the difference in thinking prospectively caused a difference in behavior. It's just as likely that the difference in thinking retrospectively reacted to a difference in behavior.

The problem becomes especially obvious in the 19th century. Oldstone-Moore's arguments tend to suffer from the fallacy of reversibility. A case in point is his assessment of the Abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, who published an 1829 anti-beard rant. Of Beards and Men would have it that facial hair was radical--so radical that even a fire-breather like Garrison couldn't stomach it. But if Garrison had published a pro-beard rant, I'll bet anyone a dollar that Of Beards and Men would have explained that facial hair was radical--so radical that it could only appeal to a fire-breather like Garrison. Heads, facial hair was radical; tails, facial hair was radical.

Then we get to the contention that "It was no mere coincidence that the era of beards [in the mid-19th century] corresponded closely with the emergence of the women's movement." Beards, according to Oldstone-Moore, represent a kind of masculine backlash. As women pushed into traditionally male preserves, men got hairy as a defensive measure. This is a classic reversible argument. No matter what happened to women, men, or facial hair, you could explain it equally well:

| Long Beards | Short Beards | |

|---|---|---|

| Women Gaining Power | "Male facial hair was an attempt to assert masculinity in the face of a threat." | "The growth of shaving reflected the increasing acceptance of feminine norms in the public sphere." |

| Women Losing Power | "Male facial hair reflected the increasing dominance of the untamed and unfeminized male." | "Men's beards were not required, because the disempowerment of women did not require a further assertion of masculinity." |

Among us soul-less reductionist left-brained narrow-minded empiricist types, there's a test for this sort of thing. Namely, you take your hypothesis and you make a falsifiable prediction. In this case, Oldstone-Moore's hypothesis would prima facie seem to predict that the 1910s and 1920s, with women's suffrage (and associated causes, such as temperance) a vigorous and ever-strengthening and occasionally even violent force, men should have felt even more threatened and grown even more luxuriant locks in response. Only . . . well . . .

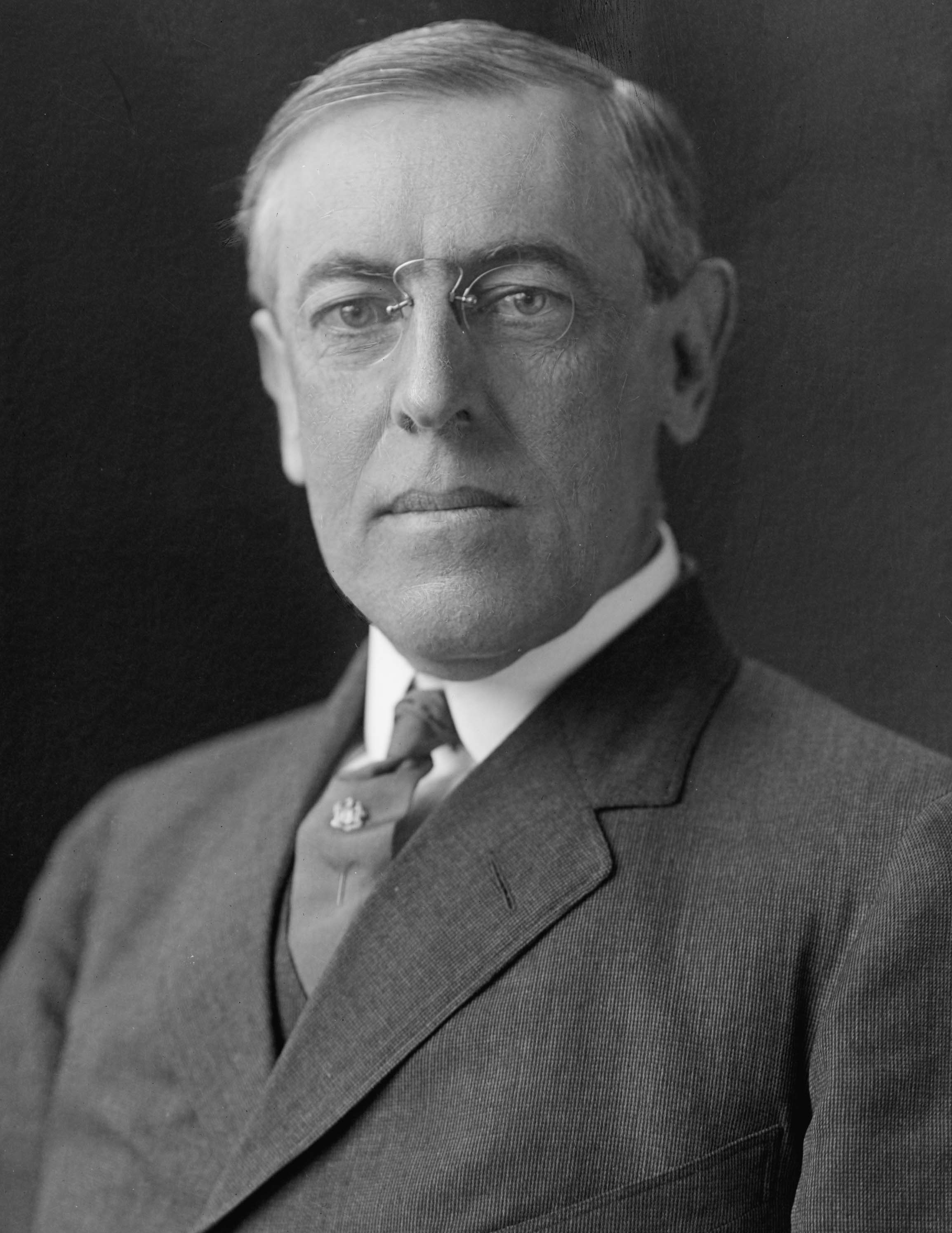

|

| Woodrow Wilson |

|

| Calvin Coolidge |

|

| Herbert Hoover |

Sunday, November 27, 2016

Book Review: Noise

Noise: A Human History of Sound and Listening

David Hendy

Sociology

I was thinking of this as a companion book for Bruce Watson's book Light. (I bought it in the same very fine bookstore, too.) By comparison, Hendy's book--though very engagingly and conversationally written--is refreshingly free from Light's literary pyrotechnics. It's also, to give a linguistic point back to Bruce Watson, less focused. That's sort of appropriate. Light is specific; we see what's in front of us. Sound is general; we hear what the world sends us.

I'm not going to try to untangle David Hendy's theses. They're present, but they're not really central to the book. The ubiquity of sound means that Hendy has to ignore as much as he includes. His organization is chronological: he proceeds through time, picking up a sound-related theme in each chapter. It's a good structure, as long as you don't pretend to believe that the theme was the meaningful sound-related thing going on at that time. There would always have been others; it's just that to make room for them Noise would have to have been three hundred thousand pages long instead of three hundred.

As an instance, take chapter 22, "The Beat of a Heart, the Tramp of a Fly". Spatially, it falls about two-thirds of the way through Noise. It begins thus:

Understand, I'm not nitpicking because I disliked Noise. On the contrary: I love this stuff! There's a companion BBC radio series which I plan to listen to. Read the book as a sampler rather than pretending that it's really any kind of true, connected "history" and you'll be fine.

David Hendy

Sociology

I was thinking of this as a companion book for Bruce Watson's book Light. (I bought it in the same very fine bookstore, too.) By comparison, Hendy's book--though very engagingly and conversationally written--is refreshingly free from Light's literary pyrotechnics. It's also, to give a linguistic point back to Bruce Watson, less focused. That's sort of appropriate. Light is specific; we see what's in front of us. Sound is general; we hear what the world sends us.

I'm not going to try to untangle David Hendy's theses. They're present, but they're not really central to the book. The ubiquity of sound means that Hendy has to ignore as much as he includes. His organization is chronological: he proceeds through time, picking up a sound-related theme in each chapter. It's a good structure, as long as you don't pretend to believe that the theme was the meaningful sound-related thing going on at that time. There would always have been others; it's just that to make room for them Noise would have to have been three hundred thousand pages long instead of three hundred.

As an instance, take chapter 22, "The Beat of a Heart, the Tramp of a Fly". Spatially, it falls about two-thirds of the way through Noise. It begins thus:

In January 1780, a sixty-year-old Edinburgh man walked slowly through the streets of his home city, wheezing and puffing rather alarmingly. As he reached Infirmary Street, just to the south of the Old Town, he turned into Surgeon's Square.This leads into the development of the stethoscope, with further excursions toward amplification of sound in general. It's a nifty little essay. The only caveat is that it's only one tiny facet of what was happening in The Wonderful World of Sound (1780-1850), and that therefore there's a lot being left out. Hendy chose to write this particular chapter, in other words, and in so doing chose not to write about the neighs of horses or the chuffing of early steam engines or the clatter of the first telegraph keys or the thunk of the guillotine during the French Revolution or the thunder of the buffalo herds in the last days of their glory or . . .

Understand, I'm not nitpicking because I disliked Noise. On the contrary: I love this stuff! There's a companion BBC radio series which I plan to listen to. Read the book as a sampler rather than pretending that it's really any kind of true, connected "history" and you'll be fine.

Tuesday, September 6, 2016

Book Review: The Book of Spice

The Book of Spice: From Anise to Zedoary

John O'Connell

Food

The Book of Spice is similar in spirit to Lingo. That is: it's a quick tour d'epicerie jaunt around the culinary back streets. It provides a good capsule overview--history, uses, legends, science, care, feeding, etc.--for a large number of entries. It's not deep, but it's entertaining. It shouldn't be read on an empty stomach. It makes me curious about vast swathes of ethic cuisine of which I know little to nothing. (Also, it would be of some practical use as a reference book.)

One caveat: John O'Connell is writing from and for a British-Isles perspective. He spends an extraordinary number of words on curry, while short-changing the New World. Aside from a good section on the chili pepper, there's virtually nothing about Mexican or other Latino cuisines. There's even less about (for example) barbeque, or Cajun, or Creole. On the other hand, some of those curry ideas sound pretty enticing.

Spice: The History of a Temptation is a deeper look at the use, sociology, and economics of the spices and the trade.

John O'Connell

Food

The Book of Spice is similar in spirit to Lingo. That is: it's a quick tour d'epicerie jaunt around the culinary back streets. It provides a good capsule overview--history, uses, legends, science, care, feeding, etc.--for a large number of entries. It's not deep, but it's entertaining. It shouldn't be read on an empty stomach. It makes me curious about vast swathes of ethic cuisine of which I know little to nothing. (Also, it would be of some practical use as a reference book.)

One caveat: John O'Connell is writing from and for a British-Isles perspective. He spends an extraordinary number of words on curry, while short-changing the New World. Aside from a good section on the chili pepper, there's virtually nothing about Mexican or other Latino cuisines. There's even less about (for example) barbeque, or Cajun, or Creole. On the other hand, some of those curry ideas sound pretty enticing.

Spice: The History of a Temptation is a deeper look at the use, sociology, and economics of the spices and the trade.

Wednesday, August 10, 2016

Book Review: Door to Door

Door to Door: The Magnificent, Maddening, Mysterious World of Transportation

Edward Humes

2016, Books, Engineering, Sociology

The subtitle has some truth in it. Door to Door is, in places, magnificent. It's often maddening, too. In the best cases this is in agreement with Edward Humes's arguments. Other times, unfortunately, it's Humes himself who's maddening. Door to Door isn't really one book, in fact. It's two books, which happen to reside awkwardly between the same pair of covers.

Book A is what I recently called an empiricist book about how transportation happens. That is, it's about the magic of moving stuff (and people, but mainly stuff) around. This book is genuinely fascinating and enlightening. It's what's described in the blurb. I would happily have read this book.

Book B is a book which should be entitled Why Cars Are Eeeevil (and How the Self-Driving Car Will Save Us All). It's a long, impassioned, well-written, impressively statistic-driven essay--I think I wouldn't be going too far in using the term "diatribe", with "rant" lurking in the wings--about Why Cars Are Evil.

I am not an unreceptive audience to this message. I read most of this book while riding commuter rail trains, which I take (in large part) because I think that cars really are evil. There's nothing wrong with this idea. I would happily have read Why Cars Are Eeeevil as well--and had many fewer reservations afterwards.

But Why Cars Are Eeeevil isn't a stand-alone; nor does it peacefully coexist with the original book, the one about logistics. You'll forgive me for observing that, in fact, it runs right over it, leaving its tire-riven corpse bleeding in the gutter. Humes gets so wound up in Why Cars Are Eeeevil that he neglects to finish the other book. His research never takes him outside of southern California. He dismisses the national freight railroad system in a sentence--a laudatory sentence, but still! One sentence! Pipelines and barges aren't mentioned at all.

Door to Door could be sliced up into a number of good Slate magazine articles. It could be split into two books, each of which would have something going for it. As one split-personality book, I'd have to rate it less "magnificent", more "maddening", and--I'm sorry to say it--something of a disappointment as well.

One of the best books ever written on the logistics of transportation is (naturally) by John McPhee: Uncommon Carriers. Rose George's 90% of Everything is also pretty good.

Edward Humes

2016, Books, Engineering, Sociology

The subtitle has some truth in it. Door to Door is, in places, magnificent. It's often maddening, too. In the best cases this is in agreement with Edward Humes's arguments. Other times, unfortunately, it's Humes himself who's maddening. Door to Door isn't really one book, in fact. It's two books, which happen to reside awkwardly between the same pair of covers.

Book A is what I recently called an empiricist book about how transportation happens. That is, it's about the magic of moving stuff (and people, but mainly stuff) around. This book is genuinely fascinating and enlightening. It's what's described in the blurb. I would happily have read this book.

Book B is a book which should be entitled Why Cars Are Eeeevil (and How the Self-Driving Car Will Save Us All). It's a long, impassioned, well-written, impressively statistic-driven essay--I think I wouldn't be going too far in using the term "diatribe", with "rant" lurking in the wings--about Why Cars Are Evil.

I am not an unreceptive audience to this message. I read most of this book while riding commuter rail trains, which I take (in large part) because I think that cars really are evil. There's nothing wrong with this idea. I would happily have read Why Cars Are Eeeevil as well--and had many fewer reservations afterwards.

But Why Cars Are Eeeevil isn't a stand-alone; nor does it peacefully coexist with the original book, the one about logistics. You'll forgive me for observing that, in fact, it runs right over it, leaving its tire-riven corpse bleeding in the gutter. Humes gets so wound up in Why Cars Are Eeeevil that he neglects to finish the other book. His research never takes him outside of southern California. He dismisses the national freight railroad system in a sentence--a laudatory sentence, but still! One sentence! Pipelines and barges aren't mentioned at all.

Door to Door could be sliced up into a number of good Slate magazine articles. It could be split into two books, each of which would have something going for it. As one split-personality book, I'd have to rate it less "magnificent", more "maddening", and--I'm sorry to say it--something of a disappointment as well.

One of the best books ever written on the logistics of transportation is (naturally) by John McPhee: Uncommon Carriers. Rose George's 90% of Everything is also pretty good.

Tuesday, July 5, 2016

Book Review: You May Also Like

You May Also Like: Taste in an Age of Endless Choice

Tom Vanderbilt

2016, Books, Psychology

You May Also Like is endlessly diverting. It is also, for a rationalist, faintly depressing. Tom Vanderbilt charges (entertainingly enougn) off in a great many different directions at once, although making sense of his results is not simple. Executive summary: people are nuts. We seem to make decisions based on everything except anything that makes sense.

For example, the conventional wisdom is that the Internet makes it possible for esoteric and idiosyncratic preferences to flourish (the so-called long-tail phenomenon). Sounds great, huh? Except that, according to Vanderbilt, it ain't so. The Internet, instead, magnifies the "signal" of mass consumption. People with more information on what's popular are more conformist, not less.

There are a lot of other examples here. Vanderbilt is good at drawing connections between seemingly-disparate findings. He's a little less good at large-scale conclusions. This is one of the few books where the epilogue, where Vanderbilt actually summarizes what he thinks he's found, is almost as informative as the main text.

Tom Vanderbilt

2016, Books, Psychology

You May Also Like is endlessly diverting. It is also, for a rationalist, faintly depressing. Tom Vanderbilt charges (entertainingly enougn) off in a great many different directions at once, although making sense of his results is not simple. Executive summary: people are nuts. We seem to make decisions based on everything except anything that makes sense.

For example, the conventional wisdom is that the Internet makes it possible for esoteric and idiosyncratic preferences to flourish (the so-called long-tail phenomenon). Sounds great, huh? Except that, according to Vanderbilt, it ain't so. The Internet, instead, magnifies the "signal" of mass consumption. People with more information on what's popular are more conformist, not less.

There are a lot of other examples here. Vanderbilt is good at drawing connections between seemingly-disparate findings. He's a little less good at large-scale conclusions. This is one of the few books where the epilogue, where Vanderbilt actually summarizes what he thinks he's found, is almost as informative as the main text.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)