Biscuit and Robin. (Robin is the one in glasses).

Cat Yin+Yang.

Happy New Year to my

Though all the scenes are based on actual events, in several instances, where primary source material was lacking, I offered my best approximation of specific details."Based on actual events," huh?

I don't know that I'd be in a rush to read another non-fiction book by Nancy Marie Brown. On the other hand, if she ever publishes any translations of those sagas, I'm there.Song of the Vikings isn't quite that, but it's the next best thing: the story of how the sagas and myths came to be written down, and the biography of the man who did the writing. It's a subject that play's to Brown's strengths (hugely evocative writing, a sense of place and time, deep knowledge, passion for the subject) and largely avoids her weaknesses (a lack of intellectual discipline).

| Long Beards | Short Beards | |

|---|---|---|

| Women Gaining Power | "Male facial hair was an attempt to assert masculinity in the face of a threat." | "The growth of shaving reflected the increasing acceptance of feminine norms in the public sphere." |

| Women Losing Power | "Male facial hair reflected the increasing dominance of the untamed and unfeminized male." | "Men's beards were not required, because the disempowerment of women did not require a further assertion of masculinity." |

|

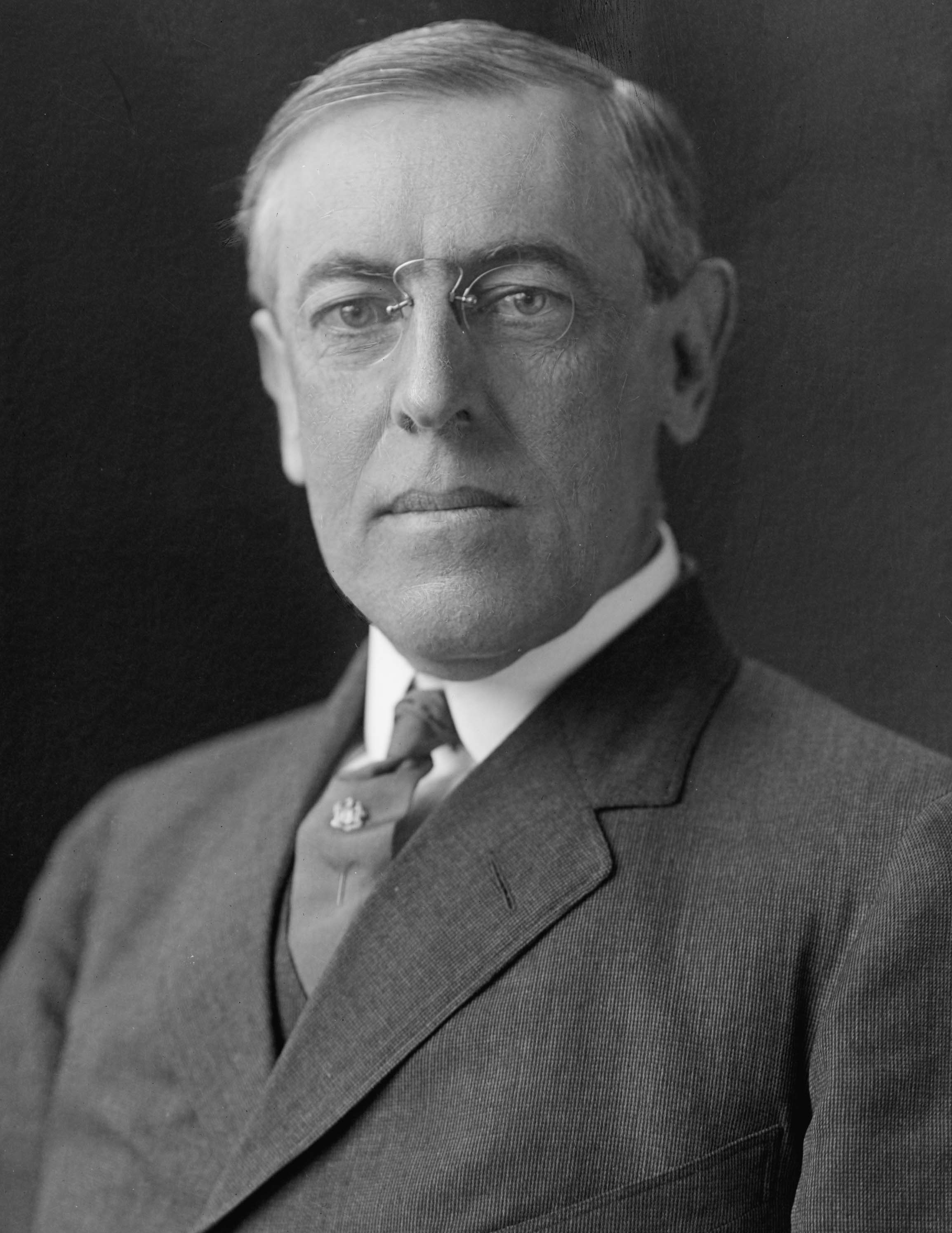

| Woodrow Wilson |

|

| Calvin Coolidge |

|

| Herbert Hoover |

| (Image hosted by the Rockwell Museum) |

In January 1780, a sixty-year-old Edinburgh man walked slowly through the streets of his home city, wheezing and puffing rather alarmingly. As he reached Infirmary Street, just to the south of the Old Town, he turned into Surgeon's Square.This leads into the development of the stethoscope, with further excursions toward amplification of sound in general. It's a nifty little essay. The only caveat is that it's only one tiny facet of what was happening in The Wonderful World of Sound (1780-1850), and that therefore there's a lot being left out. Hendy chose to write this particular chapter, in other words, and in so doing chose not to write about the neighs of horses or the chuffing of early steam engines or the clatter of the first telegraph keys or the thunk of the guillotine during the French Revolution or the thunder of the buffalo herds in the last days of their glory or . . .

Living in a capricious world means accepting that we do not live within a stable moral cosmos that will always reward people for what they do . . . We should always expect to be surprised and learn to work with whatever befalls us. If we can continue this work, even when tragedies come our way, we can begin to accept the world as unpredictable and impossible to determine perfectly . . . We can go into each situation resolved to be the best human being we can be, not for what we'll get out to it, but simply to affect others around us for the better, regardless of the outcome.OK, great. Only . . . doesn't it sound kind of similar to this?

Begin each day by telling yourself: Today I shall be meeting with interference, ingratitude, insolence, disloyalty, ill-will, and selfishness – all of them due to the offenders’ ignorance of what is good or evil. But for my part I have long perceived the nature of good and its nobility, the nature of evil and its meanness, and also the nature of the culprit himself, who is my brother (not in the physical sense, but as a fellow creature similarly endowed with reason and a share of the divine); therefore none of those things can injure me, for nobody can implicate me in what is degrading. Neither can I be angry with my brother or fall foul of him; for he and I were born to work together, like a man’s two hands, feet or eyelids, or the upper and lower rows of his teeth.The second one isn't a Chinese sage talking. No, that's Marcus Aurelius, emperor of Rome and one of the last great Stoic philosophers. Other "revolutionary" concepts in The Path sound a lot like Epicureanism, or even like classical skepticism (which is a little different from the modern understanding).

A monkey trainer was handing out nuts, saying, "You get three in the morning, and four at night." The monkeys were enraged. So he said, "All right, then, you get four in the morning and three at night." The monkeys were thrilled.This is meant to argue that it's better to adjust your way of thinking than to make yourself unhappy. That's nice. As a Westerner, though, I believe in the power of reason. It is better to have the trainer's rational understanding than the monkeys' non-rational sentiments.

She yearned for his love and approbation. She had listened dutifully, had asked the right questions, had instinctively known that this was an interest he assumed that she would share. But she realized now that the deception had only added guilt to her natural reserve and timidity, that the river had become more terrifying because she could not acknowledge its terrors and her relationship with her father more distant because it was founded on a lie.This is, as the British put it, over-egging the pudding.

Character 1: Hey, how about you give me all your money and everything you've built up and basically your entire life, and go into hibernation for a while. Do it for the sake of the human spirit.That's a nice compact example, but it's far from the weirdest one.

Character 2: Okay! Sounds like a plan!

The luxuriously-furnished entrance hall, illuminated by a glass and silver chandelier and adorned in oak wainscoting, featured built-in settee and armchairs . . . The adjacent library . . . was made entirely of mahogany bookcases, their doors lined with box-pleated silk, while its walls and ceilings were stenciled decoratively . . . The drawing room was furnished entirely in rosewood . . . the dining room [was] covered in peacock-blue wallpaper on dull yellow ground with Persian figurings . . .When Baldwin does introduce technical detail, he doesn't always do it well. Here, for example, is a description of Edison's late experiments with rubber: ". . . the specimen was treated with acetone . . . extracted with benzol. . . the acetone step was abandoned and replaced with more precise bromination . . . which essentially meant the addition of carbon tetrachloride and alcohol . . ." Unless you're a chemist, this isn't very informative; it reads to me as though Baldwin was paraphrasing some technical description that he didn't really understand either.

The impulse to conserve and move slowly, to build incrementally and protect what has already been done, is an honorable one. So is the drive to start again, to bend the energies of creation towards an unseen future. But this is also to say that both sides are wrong. Each one's error is inevitable, since it reflects an ineradicable fact of the human predicament. We live at the mercy of time and can only fail in our efforts to master it, to speed it up or slow it down.Uh, okay, A.O. If you say so. It's not clear that this helps me think about art, pleasure, beauty, or truth, though.

This [the S.S. Great Eastern] is the ship thatAside from that, The Great Iron Ship is well-written, occasionally sardonic, briskly-paced, not exhaustively deep, and well-structured as a narrative. I think Dugan pays maybe a little too much attention to the so-called "jinx" on the Great Eastern. To my mind, the real story is not the jinx but just how astonishingly it was, in the mid-19th century, people getting randomly killed or maimed in fights or crowds or just weird stuff. (Imagine someone getting killed nowadays by an accident when firing a 21-gun salute, for example. It wouldn't just be waved off!) And, of course, I want more engineering! Still, a very good book.

- Killed her designer

- Drowned her first captain

- Logged four mutinies

- Killed thirty-five men

- Survived the Atlantic's weirdest storm

- Laid the Atlantic Cable

- Sank four ships

- Made six knights

- Caused sixteen lawsuits

- Was six times at auction

- Boarded two million sightseers

- Ended as a floating circus

| Chan | Poirot |

|---|---|

| A four-horse chariot could not have dragged me in an opposite direction. | The good dog, he does not leave the scent, remember! |

| I am torn with grief to disagree. | I demand of you a thousand pardons, monsieur. |

| This last story illuminates darkness. | The affair marches, does it not? |

| Your words have obscure sound. | The word exact, you are zealous for it. |