The Great Quake: How the Biggest Earthquake in North America Changed Our Understanding of the Planet

Henry Fountain

Geology, biography

The 1906 San Francisco quake gets all the press, but the 1964 Alaska quake was bigger. How much bigger? Oh, about 90x as powerful, in terms of total energy released. The human cost was limited only by the limited population in the area. As it was, the entire city of Valdez was flattened, abandoned, and rebuilt from the ground up--four miles inland, on bedrock.

Not only that, the Alaska quake came at a crucial point in the development of geoscience. The theory of (what's now called) plate tectonics had been floating around since the 1920s; in the 1960s it was beginning to gain currency. Evidence from the Alaska earthquake provided crucial support.

Those are the two threads that Henry Fountain builds The Great Quake around. It's a nice piece of work. Fountain very sensibly chooses one primary viewpoint character for each thread--geologist George Plafker and schoolteacher Kris Madsen--with other characters weaving their ways into and out of the story. The result is one part human tragedy, one part scientific detective story.

Both parts are good, too (which doesn't always happen with this sort of book). The picture of the sheer unstoppable devastation caused by the quake is particularly vivid. Streets ripple and crack. Slabs of concrete shear off the sides of buildings. A ship, 441.5 feet long, rocks in the waves so that its brass propellor appears above the houses. Tsunamis reach, in some cases, hundreds of feet above the water line. On the scientific side, too, Fountain has chosen a very appealing main character to follow: a working-class Brooklyn kid, who fell in love with geology almost by accident (and who's still alive, at the time of this typing).

The Great Quake is a good science book for non-scientists. It's also a good sociology book for non-sociologists, and a good piece of human-interest reportage to boot. It's well worth your time.

The inevitable John McPhee has to be mentioned here, once again, both for his books about geology (collectively known as Annals of the Former World) and for his book about Alaska, Coming Into the Country. Simon Winchester's A Crack in the Edge of the World is a good account of the San Francisco also-ran.

Friday, April 27, 2018

Sunday, April 22, 2018

Short Story Teaser: "Code H"

From time to time I've offered up samples of my creative output, as we author chappies are wont to do. Here's another. Leave me a note if you'd like me to send you the whole thing. (This is still something of a draft, not necessarily the final version.)

"God damn it," said Mahoney, slamming down her coffee cup. Drips slopped over onto her desk. "Hitler's dead again."

"What's that, three this kilochron?" asked Ibekwe across the low cubicle wall.

"Four." Mahoney wiped up coffee with the back of her tie. She hated the tie. There were good things about not having to walk a temporal beat. Wearing the clothes wasn't one of them.

Ling's head popped up from Robbery, halfway across the squad room. "When is it this time?" he called.

"July '31. Why, what do you care?"

"Office pool."

"Great," said Mahoney, standing. "If you win, how about you fill out the fucking DHP-370s?"

Lieutenant Xox, a.k.a. the Loot, rolled its eyes. It had three of them. Mahoney thought this gave it an unfair advantage. Insofar as a creature that looked like a seven-foot-tall cerulean-scaled lizard could look jaundiced, it looked jaundiced.

"Another code H?" it said. "Sonofabitch. What the hell is it with this precinct, anyway?"

"It's the goddamn writers," said Mahoney. "You got sci-fi writers when you come from?"

"Not any more," said Xox, giving her a toothy grin. It had an unfair advantage in that department as well.

"Well, that shit's practically a cottage industry around here. Means every asshole who gets ahold of a chronomobile, the first thing they think is 'Hey, I'm gonna go kill Hitler.'"

Xox shrugged. "Well, it keeps us in business, I guess. When was it, by the way?"

"July 1931. Don't tell me you're in the pool too."

"Sure, but I had January '28. Anyway, that's not why I called you in. You're gonna have a ride-along on this one."

Mahoney swore fluently in twenty-third century Sparabic. It was a good language for swearing. The Loot waited, looking occasionally out the window, which was in the 1970s. For some reason Xox really liked the 1970s.

Mahoney realized she was repeating herself. She stopped.

"Sorry, Sparks," said Xox, not sounding sorry. "This came all the way from the Castle. It's the new curriculum. They want to get the cadets out walking the timestreams, show 'em how it's done. Hell, you should be all for that."

"I am, just not with me."

"I'll tell the commissioner next time we have tea. I'm sure she'll be real sympathetic. 'Til then, you get to experience the joy and camaraderie of mentoring." It turned two of its eyes towards her midsection. "Maybe you can trade grooming tips. Buddha's balls, Mahoney, it looks like you washed your tie in coffee. And get your DHP-370s in on time, for once."

Code H

"What's that, three this kilochron?" asked Ibekwe across the low cubicle wall.

"Four." Mahoney wiped up coffee with the back of her tie. She hated the tie. There were good things about not having to walk a temporal beat. Wearing the clothes wasn't one of them.

Ling's head popped up from Robbery, halfway across the squad room. "When is it this time?" he called.

"July '31. Why, what do you care?"

"Office pool."

"Great," said Mahoney, standing. "If you win, how about you fill out the fucking DHP-370s?"

#

Lieutenant Xox, a.k.a. the Loot, rolled its eyes. It had three of them. Mahoney thought this gave it an unfair advantage. Insofar as a creature that looked like a seven-foot-tall cerulean-scaled lizard could look jaundiced, it looked jaundiced.

"Another code H?" it said. "Sonofabitch. What the hell is it with this precinct, anyway?"

"It's the goddamn writers," said Mahoney. "You got sci-fi writers when you come from?"

"Not any more," said Xox, giving her a toothy grin. It had an unfair advantage in that department as well.

"Well, that shit's practically a cottage industry around here. Means every asshole who gets ahold of a chronomobile, the first thing they think is 'Hey, I'm gonna go kill Hitler.'"

Xox shrugged. "Well, it keeps us in business, I guess. When was it, by the way?"

"July 1931. Don't tell me you're in the pool too."

"Sure, but I had January '28. Anyway, that's not why I called you in. You're gonna have a ride-along on this one."

Mahoney swore fluently in twenty-third century Sparabic. It was a good language for swearing. The Loot waited, looking occasionally out the window, which was in the 1970s. For some reason Xox really liked the 1970s.

Mahoney realized she was repeating herself. She stopped.

"Sorry, Sparks," said Xox, not sounding sorry. "This came all the way from the Castle. It's the new curriculum. They want to get the cadets out walking the timestreams, show 'em how it's done. Hell, you should be all for that."

"I am, just not with me."

"I'll tell the commissioner next time we have tea. I'm sure she'll be real sympathetic. 'Til then, you get to experience the joy and camaraderie of mentoring." It turned two of its eyes towards her midsection. "Maybe you can trade grooming tips. Buddha's balls, Mahoney, it looks like you washed your tie in coffee. And get your DHP-370s in on time, for once."

Saturday, April 21, 2018

Book Review: Fatal Discord

Fatal Discord: Erasmus, Luther, and the Fight for the Western Mind

Michael Massing

Philosophy, religion, history

As with Crucible of Faith, I read this book, not because religion is among my core interests, but because I'm largely ignorant of the subject matter. In this, if for somewhat different reasons, I'm a match for the author. "I had never read the New Testament," he says in an afterword, "could not distinguish Peter from Paul, knew little about the birth of Christianity."

The result is a pretty good matchup, and a pretty good book. Massing's explicit mission is to rescue Erasmus from Martin Luther's vast penumbra. Erasmus of Rotterdam is a name that invokes vague familiarity in the well-read (I certainly couldn't have told you any details about him); Lutheran jokes, by contrast, were a staple of A Prairie Home Companion. Yet the battle between their worldviews is as lively as ever.

Luther is the one who got famous as the champion of individual judgment. "I cannot and will not recant anything, since it is neither safe nor right to go against conscience," he's recorded as saying--in the face of a very real possibility that he would be burned at the stake for saying it. Courageous, yes; and yet, in truth, Luther ended up by furiously denying that other people might use their consciences. He feuded savagely with everyone, other reformers most especially included. It wasn't really "scripture and only scripture" that he stood for: it was "scripture according to the understanding of Martin Luther, and nobody else."

By contrast, Erasmus--though not always a model of sweetness and light in his writing--was closer to the "can't we all get along" camp. For this, he was roundly vilified by everyone, Luther included. He seems to have been prickly and egocentric, and sometimes vituperative--it was a vituperative age, literarily speaking--but, unlike Luther, he didn't set himself up as the sole arbiter of a singular truth, and he generally called for his foes to be convinced rather than disemboweled. (Massing quotes a letter in which Erasmus frankly admits that he's a coward who has no wish to be a martyr, no stomach for fighting to the death; it made me like him rather more than otherwise!)

In his last chapters, Massing follows the Luther/Erasmus split into the modern world. Luther's insistence on a single truth and a single interpretation of it is obviously relevant to modern American politics, for example; so his his insistence on the right of the individual, not the authorities, to seek it.. The Erasmian tradition shows up among those who argue for compromise and arbitration as an alternative to war, as well as for those who emphasize inner rather than outer piety.

This is a pretty interesting thread. All the same, it would be more accurate to describe Luther and Erasmus as torchbearers for these ideas, rather than originators. The dueling perspectives themselves are, I think, universal. To take one modern analogy that Massing doesn't make, his account of the schisms and savageries within the post-Luther reform movement remind me of nothing so much as the current upheaval in the Islamic world. Violent peasant armies spring up, seemingly overnight, and sweep over large swathes of territory. Sects which are in theory united against a common enemy spent more and more of their time quarreling bitterly with each other. Firebrand preachers give rise to to even more firebrand-ish preachers, many of whom split from their progenitors. Trivial points of doctrine start wars. Ultra-puritans rail against music, against images, against modernism. The voices of moderation go unheard, even persecuted. 16th-century Germany, or the 21st-century Arab world? It could be either.

Thought-provoking, no? So, as I said, Fatal Discord is pretty good--intellectually stimulating, readable enough, and thorough. It even gets mildly exciting in spots. As it goes on, the book does lose steam somewhat. Luther dominates--he's just more colorful--and at times Fatal Discord forgets its intellectual core and descends into a straightforward biography/history. At 800 pages, it's probably too long and too detailed, and certainly not for the faint of heart. If it doesn't entirely succeed in its primary goal of rehabilitating Erasmus, it at least gives us an insight into why he was so important at the time.

For a much more modern and very readable philosophers' smackdown tale, try the excellent Wittgenstein's Poker.

Michael Massing

Philosophy, religion, history

As with Crucible of Faith, I read this book, not because religion is among my core interests, but because I'm largely ignorant of the subject matter. In this, if for somewhat different reasons, I'm a match for the author. "I had never read the New Testament," he says in an afterword, "could not distinguish Peter from Paul, knew little about the birth of Christianity."

The result is a pretty good matchup, and a pretty good book. Massing's explicit mission is to rescue Erasmus from Martin Luther's vast penumbra. Erasmus of Rotterdam is a name that invokes vague familiarity in the well-read (I certainly couldn't have told you any details about him); Lutheran jokes, by contrast, were a staple of A Prairie Home Companion. Yet the battle between their worldviews is as lively as ever.

Luther is the one who got famous as the champion of individual judgment. "I cannot and will not recant anything, since it is neither safe nor right to go against conscience," he's recorded as saying--in the face of a very real possibility that he would be burned at the stake for saying it. Courageous, yes; and yet, in truth, Luther ended up by furiously denying that other people might use their consciences. He feuded savagely with everyone, other reformers most especially included. It wasn't really "scripture and only scripture" that he stood for: it was "scripture according to the understanding of Martin Luther, and nobody else."

By contrast, Erasmus--though not always a model of sweetness and light in his writing--was closer to the "can't we all get along" camp. For this, he was roundly vilified by everyone, Luther included. He seems to have been prickly and egocentric, and sometimes vituperative--it was a vituperative age, literarily speaking--but, unlike Luther, he didn't set himself up as the sole arbiter of a singular truth, and he generally called for his foes to be convinced rather than disemboweled. (Massing quotes a letter in which Erasmus frankly admits that he's a coward who has no wish to be a martyr, no stomach for fighting to the death; it made me like him rather more than otherwise!)

In his last chapters, Massing follows the Luther/Erasmus split into the modern world. Luther's insistence on a single truth and a single interpretation of it is obviously relevant to modern American politics, for example; so his his insistence on the right of the individual, not the authorities, to seek it.. The Erasmian tradition shows up among those who argue for compromise and arbitration as an alternative to war, as well as for those who emphasize inner rather than outer piety.

This is a pretty interesting thread. All the same, it would be more accurate to describe Luther and Erasmus as torchbearers for these ideas, rather than originators. The dueling perspectives themselves are, I think, universal. To take one modern analogy that Massing doesn't make, his account of the schisms and savageries within the post-Luther reform movement remind me of nothing so much as the current upheaval in the Islamic world. Violent peasant armies spring up, seemingly overnight, and sweep over large swathes of territory. Sects which are in theory united against a common enemy spent more and more of their time quarreling bitterly with each other. Firebrand preachers give rise to to even more firebrand-ish preachers, many of whom split from their progenitors. Trivial points of doctrine start wars. Ultra-puritans rail against music, against images, against modernism. The voices of moderation go unheard, even persecuted. 16th-century Germany, or the 21st-century Arab world? It could be either.

Thought-provoking, no? So, as I said, Fatal Discord is pretty good--intellectually stimulating, readable enough, and thorough. It even gets mildly exciting in spots. As it goes on, the book does lose steam somewhat. Luther dominates--he's just more colorful--and at times Fatal Discord forgets its intellectual core and descends into a straightforward biography/history. At 800 pages, it's probably too long and too detailed, and certainly not for the faint of heart. If it doesn't entirely succeed in its primary goal of rehabilitating Erasmus, it at least gives us an insight into why he was so important at the time.

For a much more modern and very readable philosophers' smackdown tale, try the excellent Wittgenstein's Poker.

Thursday, April 19, 2018

Postscript

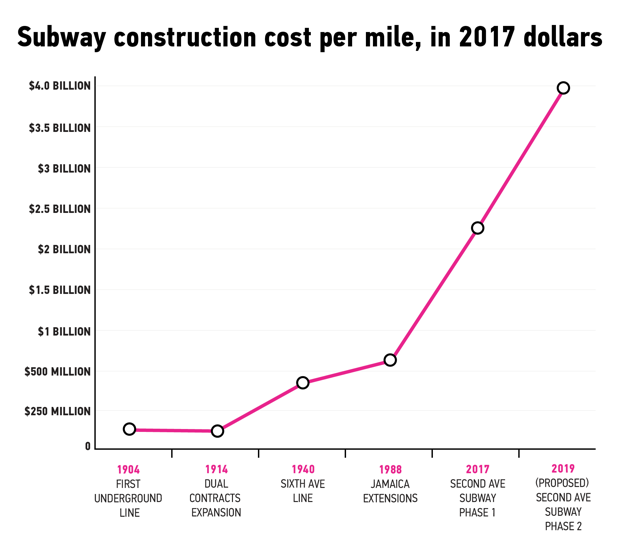

As an addendum to my recent cri de coeur, I offer this chart:

Note that this chart is inflation-adjusted. I took it from this article, which is well worth reading.

Note that this chart is inflation-adjusted. I took it from this article, which is well worth reading.

Friday, April 13, 2018

Book Review: Silk Parachute

Silk Parachute

John McPhee

Essays

John McPhee may well be America's greatest living non-fiction writer. This isn't his greatest work, but it's pretty good. These are mostly short pieces, mostly autobiographical, several dealing with sports. The best of them is "Season on the Chalk," which glides seamlessly, McPhee-fashion, across the geology of southeastern England, its extensions and permutations, French winemaking, the extinction of the dinosaurs, and other such fascinating whatnot. It's like a non-fiction version of Garrison Keillor's "News from Lake Wobegon". If you've never read McPhee, this isn't the best place to start, but it's not the worst either.

John McPhee

Essays

John McPhee may well be America's greatest living non-fiction writer. This isn't his greatest work, but it's pretty good. These are mostly short pieces, mostly autobiographical, several dealing with sports. The best of them is "Season on the Chalk," which glides seamlessly, McPhee-fashion, across the geology of southeastern England, its extensions and permutations, French winemaking, the extinction of the dinosaurs, and other such fascinating whatnot. It's like a non-fiction version of Garrison Keillor's "News from Lake Wobegon". If you've never read McPhee, this isn't the best place to start, but it's not the worst either.

Monday, April 9, 2018

Book Review: Tiny Stations

Tiny Stations: An Uncommon Odyssey Through Britain's Railway Request Stops

Dixe Wills

Trains, travel

It's even more like the usual than usual. To appreciate Tiny Stations, you'll need:

I should add, furthermore, that a relaxed attitude towards strict factual accuracy might be of assistance here. Wills swallows some blatantly urban-legend (or actually rural-legend, but it's the same thing really) anecdotes without a blink, and his personal commitment to truth in the face of a good story is open to question--he questions it himself.

If you're one of the dozen or so Americans whose response to the above is "Well, I've got to read that!", please drop me a line, if your ward attendants are willing. We'll have a lot in common.

Dixe Wills

Trains, travel

It's even more like the usual than usual. To appreciate Tiny Stations, you'll need:

- A high tolerance for a peculiarly English form of arch humor. Possibly Dixe Willis was savaged by Bill Bryson's Notes From a Small Island at an impressionable age, but he raises smiles where Bryson achieves guffaws.

- At least a passing familiarity with the British landscape. Tiny Stations is entirely undefiled by color photographs, and the few black-and-white images are small and a bit grainy. In a book that's more or less defined as "what I saw when I got off at Little-Snoodlington-in-the-Quagmire", good visuals are a must.

- A deep affection, not merely for trains--any fool could have that--not merely for train travel, but for the idea of train travel. Taking train trips can be jolly good fun. Reading about other people's train trips is not an endeavor that should be undertaken without plenty of time and a high tolerance for discursiveness.

I should add, furthermore, that a relaxed attitude towards strict factual accuracy might be of assistance here. Wills swallows some blatantly urban-legend (or actually rural-legend, but it's the same thing really) anecdotes without a blink, and his personal commitment to truth in the face of a good story is open to question--he questions it himself.

If you're one of the dozen or so Americans whose response to the above is "Well, I've got to read that!", please drop me a line, if your ward attendants are willing. We'll have a lot in common.

Sunday, April 1, 2018

Book Review: The Tale of the Dueling Neurosurgeons

The Tale of the Dueling Neurosurgeons: The History of the Human Brain as Revealed by True Stories of Trauma, Madness, and Recovery

Sam Kean

Biology, psychology

Sam Kean's books are much of a muchness. His gifts as a writer include a witty, colloquial style; good organization; and a tremendous gift for using entertaining anecdotes to illuminate and explain the larger story. That describes The Tale of the Dueling Neurosurgeons in a nutshell.

The book is cleverly structured. Instead of sticking to a strict chronological sequence, Kean makes each chapter deals with a specific part of the brain. At the same time, he manages to build up his information in a coherent, simpler-to-more-complex sequence--you won't see any of those vexatious "(as we shall explain further in Chapter 37)" interpolations that mar lesser works. The result is both entertaining and genuinely informative.

It doesn't hurt, of course, that there's a genuine if creepy fascination to Weird Brain Facts. To his credit, Kean mostly avoids the temptation to turn the book into a literary freak show; he treats the subjects of his stories with measured compassion. He also does well with character portraits of scientists, materially aided by a wealth of juicy material. Some of it, be it noted, is not for the faint of stomach.

Ultimately, though, it all comes down to Weird Brain Facts. They're weirder than you can possibly imagine. Not the least of The Tale of the Dueling Neurosurgeons's achievements is that it will make you seriously question what you imagine that you know about your "self."

The grand seigneur of this subject is Oliver Sacks, whose best-known work is The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat (I'm also partial to Musicophilia).

Sam Kean

Biology, psychology

Sam Kean's books are much of a muchness. His gifts as a writer include a witty, colloquial style; good organization; and a tremendous gift for using entertaining anecdotes to illuminate and explain the larger story. That describes The Tale of the Dueling Neurosurgeons in a nutshell.

The book is cleverly structured. Instead of sticking to a strict chronological sequence, Kean makes each chapter deals with a specific part of the brain. At the same time, he manages to build up his information in a coherent, simpler-to-more-complex sequence--you won't see any of those vexatious "(as we shall explain further in Chapter 37)" interpolations that mar lesser works. The result is both entertaining and genuinely informative.

It doesn't hurt, of course, that there's a genuine if creepy fascination to Weird Brain Facts. To his credit, Kean mostly avoids the temptation to turn the book into a literary freak show; he treats the subjects of his stories with measured compassion. He also does well with character portraits of scientists, materially aided by a wealth of juicy material. Some of it, be it noted, is not for the faint of stomach.

Ultimately, though, it all comes down to Weird Brain Facts. They're weirder than you can possibly imagine. Not the least of The Tale of the Dueling Neurosurgeons's achievements is that it will make you seriously question what you imagine that you know about your "self."

The grand seigneur of this subject is Oliver Sacks, whose best-known work is The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat (I'm also partial to Musicophilia).

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)